For the past year and a half, I’ve been illustrating for The Bible Project, a non-profit here in Portland that creates short, educational, animated videos about the bible. Though this is a contracted position, it’s effectively a full-time job for me. It’s the gig that finally pried me away from my editorial position at Dark Horse Comics last September.

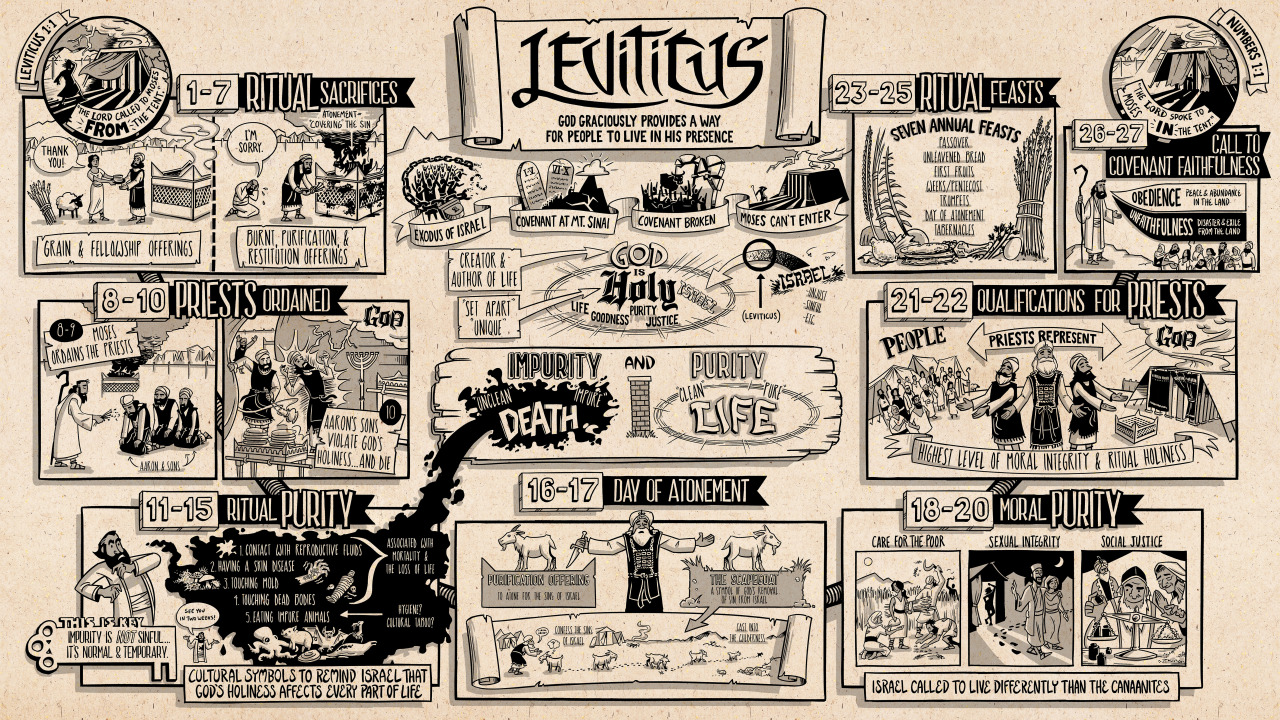

Specifically, I’ve been drawing for the “Read Scripture” series, which examines each biblical book’s structure and message. That means I drew an enormous, poster-sized diagram for almost every book of the bible! (The exceptions: Exodus, Joshua, Samuel, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job, Matthew, 1 Corinthians, and Hebrews were drawn by the incomparable Mac Cooper; Ruth, Esther, and Ephesians were drawn by Robert Peréz.) You can view all the videos that have been released so far HERE.

I don’t write these videos; the extensive research and voiceover are the work of Tim Mackie (who also officiated my wedding!). Also, I’m not responsible for the videos’ lively animation…a team of awesome motion graphics artists are responsible for making my static drawings come alive. It’s a collaboration for sure.

I just finished drawing Revelation last month (the video won’t come out until 12/15), so I’ve been trying to gather some of my thoughts on what this experience has taught me. The lessons learned are too many to even list, but a few stood out.

A NATION OF FIERCE COUNTENANCE

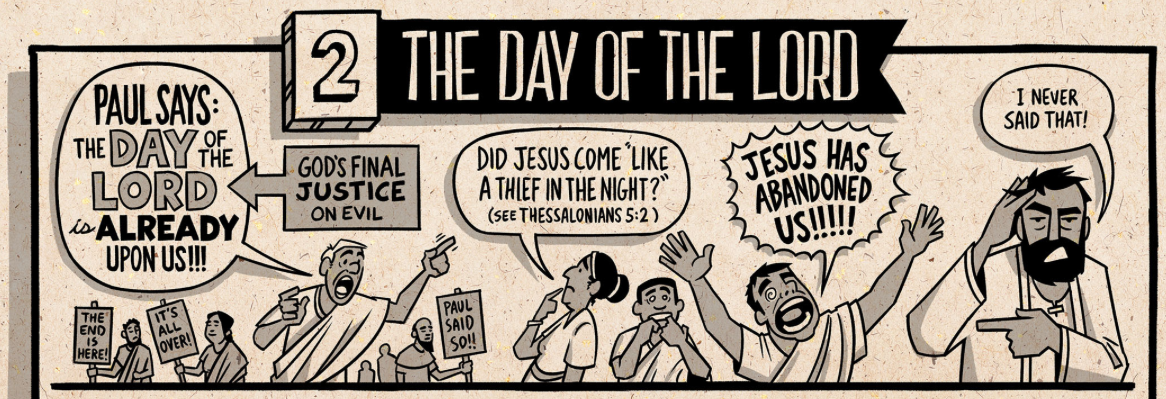

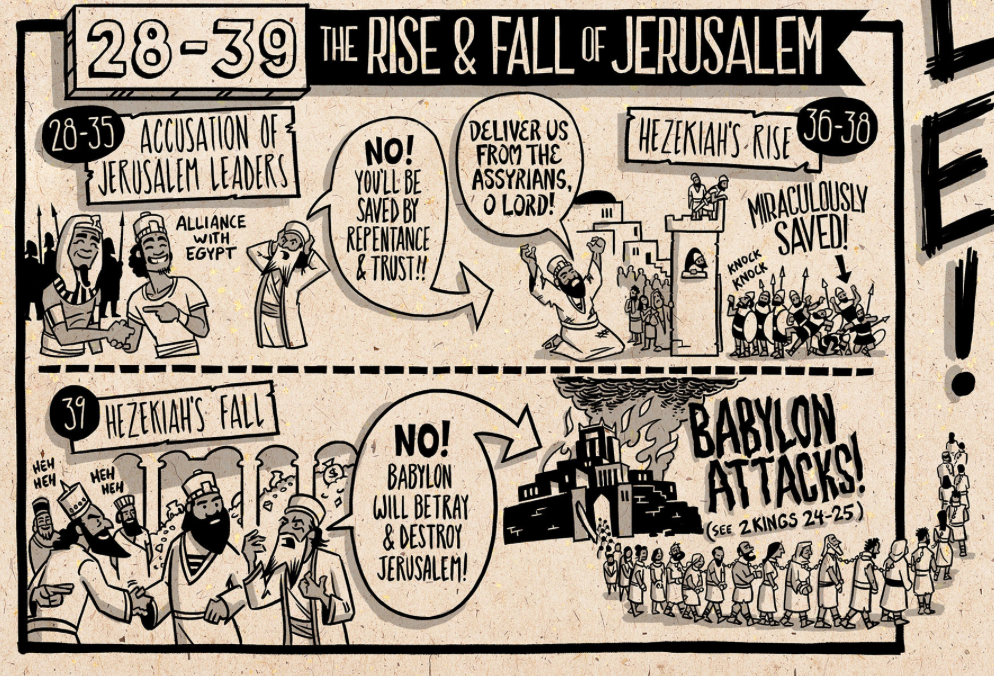

As an artist and storyteller, I enjoy the challenge of subtlety…restrained expressions, telling gestures, delicate shifts of body language that speak volumes. But in Read Scripture, subtlety goes out the window (screaming as it plummets ten stories in a waterfall of glass shards.)

Because it would only be onscreen for a few seconds, each image had to “read” instantaneously, which meant I had to really be a cartoonist. Angry people stomp and clench their fists. Proud people lift their chins skyward, hands on their hips. Sad people collapse in tearful despair. Happy people lift their hands in joyful celebration. It’s downright vaudevillian!

In a strange way, though, it’s actually appropriate to the ancient, biblical style of writing, where characters usually fume with rage or turn white with fear. Of course these actual humans were multifaceted, complex people whose emotions were no doubt inscrutable at times…but the biblical writers did not have the tools of 19th and 20th century literature at their disposal to depict this. Even if they had wanted to, they wouldn’t have known how to write novelistic prose, dramatizing the interior lives of their characters–a style we’re so used to today. But my guess is, they may not even have wanted to…often, they’re making their point through deliberate exaggeration, stark juxtapositions, or biting satire.

I think these over-the-top emotional displays work nicely in a cartoony style, but they can feel disjointed when portrayed more “realistically”…ever see one of those bible movies where everything feels so melodramatic? Naturalistic cinema cannot sustain the fevered emotional rush of adapting ancient writing literally.

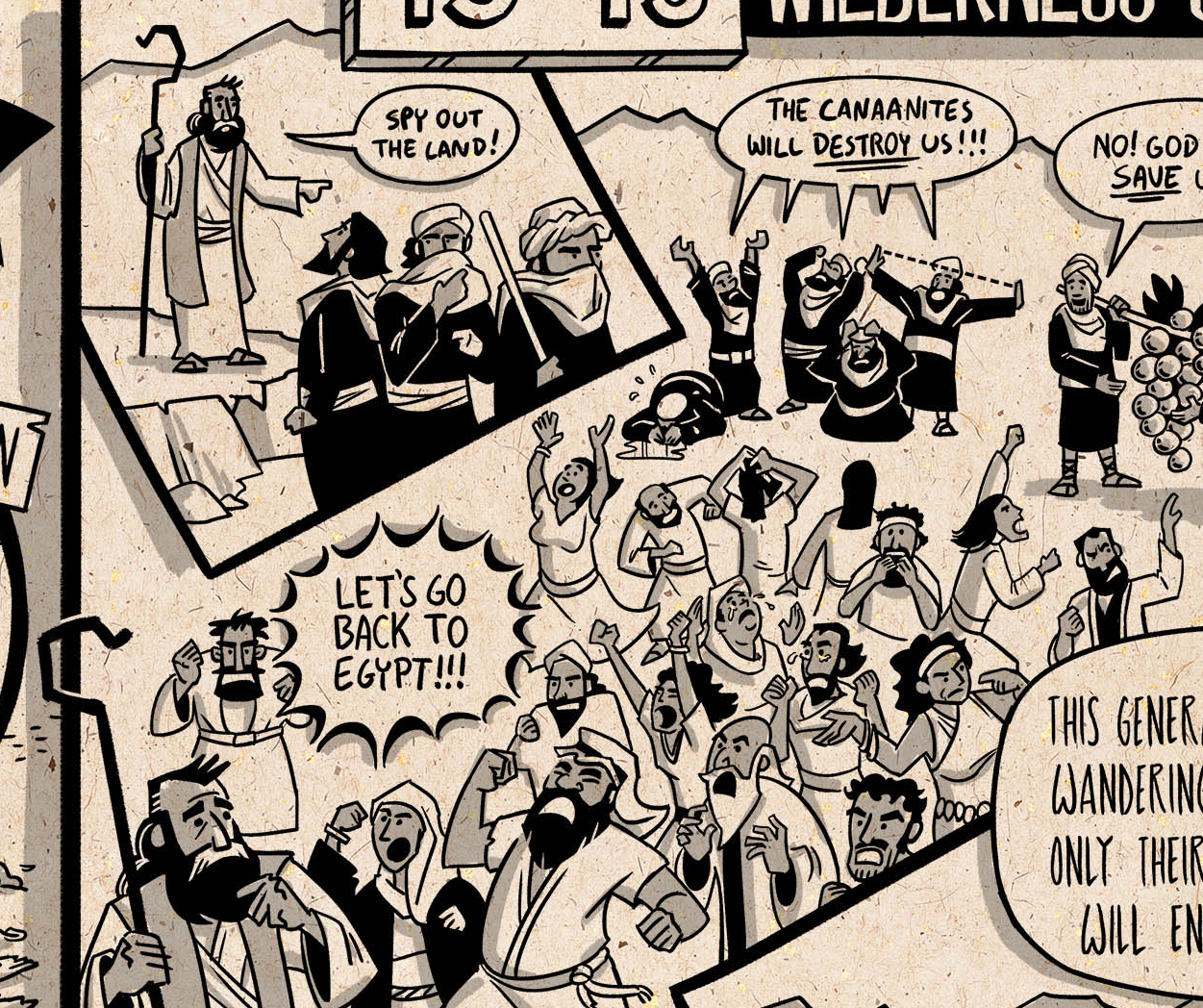

MULITITUDES, MULTITUDES

Read Scripture videos feature a LOT of crowds. Early on, I started employing the technique of using a moving crowd to depict a migration of people (into or out of exile, etc.). I also sometimes use a crowd to depict changing moods, so that people on the left are (for instance) idolatrous, people in the middle are reconsidering, and people on the right have adopted true worship. This is nothing more than the ol’ comics sleight-of-hand whereby distance translates to time.

But pouring SO much time into rendering out these Where’s-Waldo-like crowds has also given me new perspective on the story of the bible. Like all of my peers in the history department at Columbia, I had quickly discarded the old-fashioned “great man” theories of history in favor of modern approaches that analyze masses of people (social, political, and institutional history, class history, etc.). Through this lens, the “bible stories” of my youth—heroic tales about Moses, David, or Paul—seemed hopelessly antiquated.

But while there certainly are moralizing character studies in the Old and New Testaments, there’s also a LOT of social history. Even if it’s not right on the surface, the bible is always talking about shifts in politics, in economics, in popular and institutional religion, military alliances, and even more boring things like agricultural policy. Laborious as it sometimes was, drawing out these crowds felt like a way of bringing the societal element of these laws, prophecies, and letters to the forefront. We’re talking about the history of an entire nation here…a history that can’t be told without also delving into the history of other, neighboring powers!

The crowd scenes also offer a chance to recognize all the nameless, unsung figures of biblical history, especially women. They don’t often get their due recognition, but they were ALWAYS THERE, every step of the way.

GODS OF SILVER AND GOLD

One of the funnest (most fun?) parts of drawing Read Scripture was doing the preliminary visual research. I always tried to keep myself informed on the proper fashion and architecture for the location and time period…even if this often got distilled into super-simple cartoons. (sorry, Corinthian columns!)

I can’t tell you how many times I had to draw Ba’al, Ashera, Marduk, and their ilk. Idolatry is such persistent theme in the prophets (I’m not talking about metaphorical, Tim Keller idolatry…I mean actual sculpture-worship) that it’s often perplexing and boring to modern audiences. I think it may even be impossible for us to understand what an enormous religious innovation the Jewish rejection of idols was in its day—and that’s because we are now living in the legacy of that rejection.

So it was pretty uncomfortable when I found myself drawing cherubim on top of the Ark or on the walls of the temple. For a people who forbade graven images of god, Israel sure drew a lot of angels! Perhaps I had always projected the stricter iconoclasm of a later era onto early Israel.

What made it click was when I drew the vision of god’s chariot from Ezekiel chapter one. Tim helped a lot by providing me with museum-catalog images of contemporaneous iconography from Canaan, Babylon, and Israel’s other neighbors. He wanted to emphasize that Ezekiel’s vision was not an insane acid trip…that it was informed by the visual culture of his day. (In the same way, when I have dreams, whatever their content, they assume the form of Hollywood movies and television shows.)

The extreme care Ezekiel takes to avoid directly saying “I saw God” (“This was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of God”) indicates, to me, his own self-awareness that his descriptions, however divinely inspired, are nevertheless supplied by his own human language. And their very inadequacy is almost the point: the implausibility of God’s chariot emphasizes its own poetic and metaphorical nature.

MAN LOOKETH ON THE OUTWARD APPEARANCE

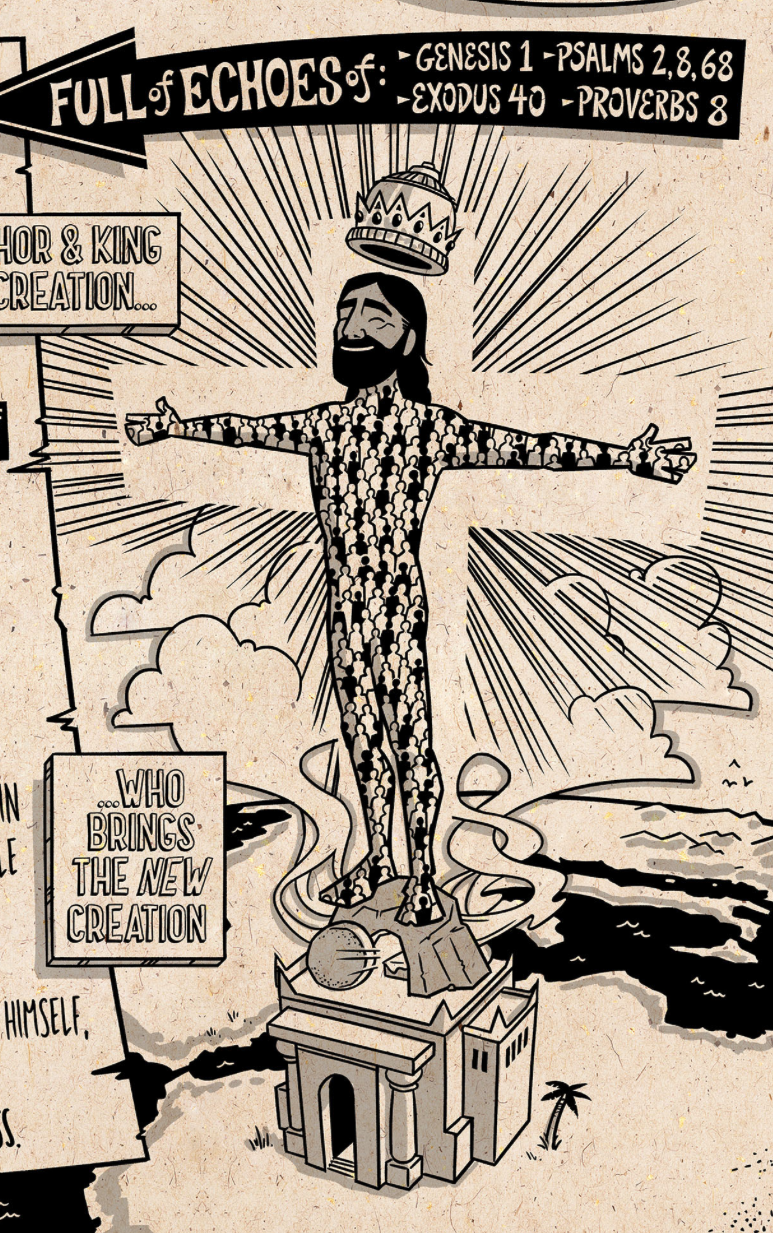

This brings me to the aspect of the Read Scripture series that I find hardest to articulate. It has to do with the deliberately literal depiction of poetic metaphor. Sometimes, as in the case of Song of Songs, this is done for laughs. But more often, I think we did it to intentionally introduce an element of disconnect into our explanation…to cause a cognitive stumble.

Whatever it means for Christ to be the head of his body, the church, it so clearly doesn’t mean literally this. The absurdity of the image rubs your nose in the metaphor and forces you to regard it afresh. It’s always tempting when you hear an overused “churchy” phrase (“We are justified by faith!” “Jesus is the messiah!” etc.) to accept it blandly and move along. Pause! Think about the message and what it’s really saying.

Cliché, art’s great enemy, is also the enemy of evangelism. Each generation invents new ways to expound upon the gospel, but yesterday’s engaging turn of phrase calcifies into today’s tedious platitude. For instance, I’m getting really tired of hearing about the importance of “my relationship with God,” a phrase ovetaxed almost to the point of uselessness (at least for me and many of my friends). But the Christians who first began speaking in this way were invigorating an enervated church! Of course, the same thing is true of visual art, which is another type of language.

Biblical language shouldn’t function as a shortcut to bypass consideration. On the contrary, every metaphor is a gateway to greater study and contemplation! This is the sweet spot for me, and my favorite thing about The Bible Project, because it combines a lot of what I love most about art with what I think is most important about evangelism: finding new ways to infuse very old ideas with fresh energy.

CLOSING THOUGHT

It’s JESUS’S. Not “Jesus’.” You wouldn’t say “I’m going to Gus’ house,” or “Today is Chris’ birthday.” So why doesn’t Jesus get an apostrophe-s? Tolerating this for sixteen months has been an exercise in charity!